The Arrival of Helene

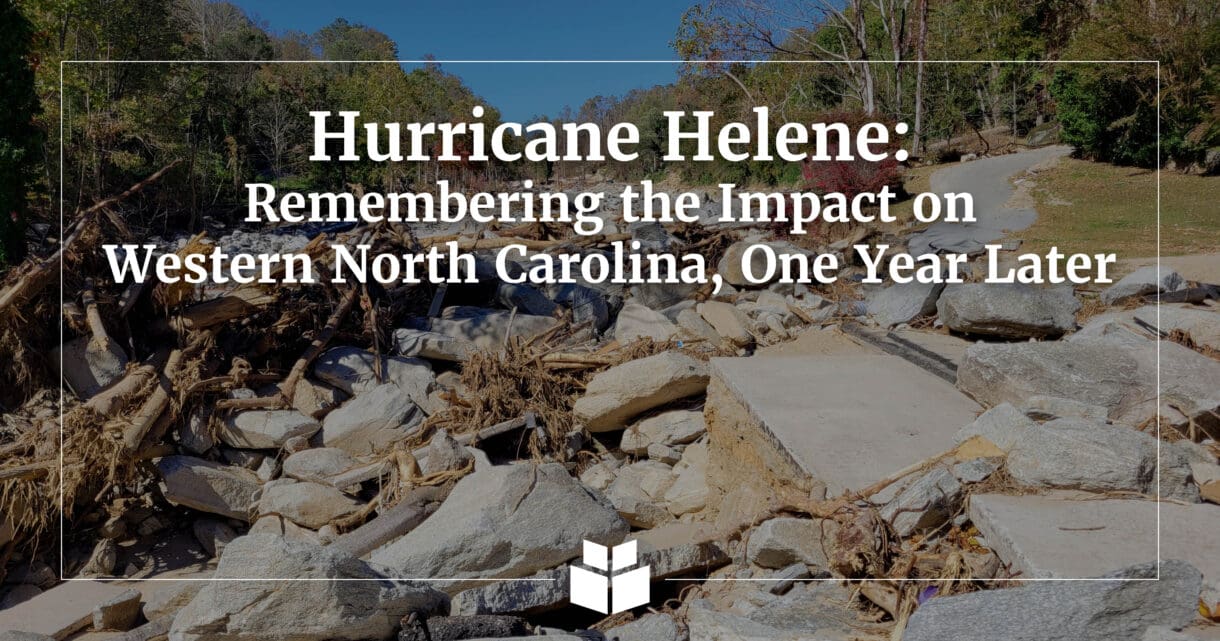

On the evening of September 27, 2024, Hurricane Helene made landfall along the Gulf Coast before turning inland and surging toward the Appalachian Mountains. By the early morning hours of September 28, the storm had reached Western North Carolina (WNC).

But Helene was not a single flash event. The region had already endured days of continuous rainfall leading up to landfall, leaving the ground saturated and river levels elevated. The results were catastrophic when Helene’s bands added another 10–20 inches of rainfall across the mountains (with localized totals over 20 inches, according to the National Weather Service).

The relentless rain not only swelled rivers and creeks beyond their banks but also destabilized hillsides, triggering numerous landslides. The steep geography of the Blue Ridge amplified the danger, funneling water into narrow valleys and washing out roadways that residents depended on for evacuation and emergency services.

The Storm’s Toll on the Region

Hurricane Helene left behind more than damaged roads and broken utilities, it claimed lives across WNC. By mid-2025, the state had confirmed 108 storm-related fatalities in North Carolina, most of them in the western mountains where flash flooding and landslides struck hardest

As Helene poured relentless rain across Buncombe, Yancey, Mitchell, Rutherford, and surrounding counties, flash flooding destroyed bridges, severed highways, and isolated entire towns. The French Broad River crested at record levels, while the Swannanoa, Pigeon, and Toe Rivers overtopped their banks. Landslides buried sections of highway and rail, while floodwater overtook schools, homes, and businesses.

Approximately 180 public drinking water systems across WNC were closed in early October, and nearly 100 wastewater plants were either offline, damaged, or without power. The North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) provided on-the-ground technical support to help restore operations, while also coordinating with the EPA to sample more than 1,500 private wells in Buncombe and Watauga counties to ensure safe drinking water.

Entire communities were cut off. More than 200,000 power outages left residents in the dark, while water and sewer systems failed, raising urgent public health risks. Cell towers and communication lines went down, leaving emergency responders scrambling to coordinate aid.

“I remember it being incredibly quiet at night, there were no lights and with the exception of a lone generator or two, there were no sounds,” recalls WithersRavenel Funding Team Lead, North Carolina, Megan Powell. “It was a stark contrast from during daylight hours, where all you heard was the sound of chainsaws and people working together to clean up their yards and helping their neighbors.”

The devastation reshaped the geography of WNC. Places once familiar to residents were rendered unrecognizable, and the reality of recovery loomed large even after the skies cleared.

The Days After Helene

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Helene, WithersRavenel mobilized to provide emergency surveying and engineering services. While many of our staff had experience responding to natural disasters, the magnitude and extent of the damage tested our teams in ways few had ever encountered.

Local governments across Western North Carolina were not unprepared. Emergency response and continuity plans were in place, and communities had experience managing severe weather events. But Helene delivered rainfall, flooding, and landslides on a scale that exceeded those frameworks. The event revealed gaps that only become visible in the most extreme conditions, when existing resources, personnel, and infrastructure are stretched beyond their limits.

DEQ staff ultimately mapped more than 2,500 landslides across the mountains. Hundreds of dams sustained damage, and one high-hazard dam, the Lake Craig Dam on the Swannanoa River, breached. Meanwhile, more than 166 temporary debris staging sites were activated to handle downed trees, hazardous materials, and contaminated waste left in Helene’s wake.

Still, amid the disruption, moments of resilience and connection emerged. As WithersRavenel teams worked to restore essential services, residents across the mountains leaned on one another to endure the day-to-day realities of life without power, water, or communication.

“There was a sense of community that was not as strong before; neighbors learned each other’s names and spent time sharing what little tidbits of news that we might have learned that day,” Powell added. “When you left your house, you put a little note on your door to let friends who might stop by know that you were safe and had gone out in search of water or food. People came together to cook what food they had in their refrigerators and cabinets on grills and over the fire. Even when you were stuck in traffic that was slow-moving due to no stoplights, people rolled down their windows and conversed with strangers.”

Lessons Learned

One year later, the memories of Hurricane Helene remain raw. For residents, the storm is remembered not only for its destruction but also for the resilience shown in the days and months that followed. Helene exposed vulnerabilities in transportation networks, utilities, and communication systems that must be addressed if mountain communities are to withstand the storms yet to come.

The response over the past year has demonstrated the importance of collaboration. Local governments, private consultants, and state agencies like the North Carolina DEQ have worked side-by-side to restore services and invest in the future. DEQ alone has secured more than $800 million in state and federal recovery funds, with nearly $200 million already awarded to support rebuilding efforts, restore water systems, and strengthen critical infrastructure against future floods.

Lessons Learned

- Critical infrastructure is only as strong as its most vulnerable link.

- Planning for redundancy saves lives.

The work is far from over. Communities like Spruce Pine, Chimney Rock, and Montreat have only begun the long process of rebuilding. In the next article, we’ll highlight these recovery stories, how wastewater treatment systems were brought back online in weeks, how transportation corridors were remapped using advanced survey technology, and how towns are navigating the FEMA process to fund long-term recovery.

Because rebuilding is more than replacing what was lost. It’s about ensuring that when the next storm comes, WNC is stronger and safer.