Introduction

Of the major asset classes office, retail, multifamily, hospitality, and industrial flex and industrial buildings operate most behind the scenes. That said, for most of us, industrial assets might have a greater impact on our daily lives than any other. In the following article, I am going to cover the basics of the industrial asset class, Industrial 101. We will cover what industrial space is, why it is important, key development and investment factors, the state of the market, and more.

For this primer, I have called on a few experts in the field: Ed Brown with NAI Tri Properties, Valerie Dunn with Edgewater Ventures, and Nathan Robb with Merritt Properties.

If you have any question or comments, I’d love to hear from you, please reach out to me at jbyrne@withersravenel.com.

Meet the Experts

Ed Brown, CCIM, SIOR

Ed Brown, CCIM, SIOR

Executive Vice President, NAI Tri Properties

With over three decades in the commercial real estate business in Wake, Durham, and surrounding counties, Ed is recognized as a consistent top-performing broker. He has earned awards and deals in all property categories, including industrial, flex, R&D facilities, and land. He currently leads NAI Tri Properties’ industrial brokerage team and is adept at handling all real estate transactions, representing landlords and sellers as well as tenants and buyers to achieve their real estate goals.

Valerie Dunn

Valerie Dunn

Associate, Edgewater Ventures

Valerie Dunn works on Edgewater’s Industrial and Innovation platforms assisting with acquisitions and asset management. She currently oversees nearly 3 million square feet of industrial and office product, where she is on the leading edge of tenant relationships, budgeting, asset optimization, and interfacing with property management teams. Prior to joining Edgewater Ventures, Valerie helped lead a strong team at HFF (now JLL) in the Capital Markets Group. Additionally, she is distinguished as a Certified Public Accountant (CPA).

Nathan Robb

Nathan Robb

Vice President of Construction and Development, Merritt Properties

Nathan Robb has been involved in the construction and real estate development arena since 2001. After completing his Bachelor of Architecture degree at UNC Charlotte, he joined Merritt Properties full time in 2006. His portfolio of work covers a wide array of projects, from urban adaptive re-use, mixed-used planned developments, mid-rise office/medical office, data centers, processing/manufacturing facilities, and light industrial developments. His experience includes land acquisition, feasibility, design, entitlement, construction management, and team building. Hailing from Baltimore, his current role as a Vice President of Construction and Development includes overseeing 2 million square feet (and growing) of development in Merritt’s newest expansion into the Triangle region.

What are industrial buildings?

The industrial asset class covers a wide range of building types. On the small end you have single-bay flex suites and standalone owner-occupied spaces. On the large end you have high bay bulk storage facilities that are millions of square feet and multiple stories tall.

The simplest flex buildings are often individual bays that people could lease,” where “they would have a bathroom, an office, a garage door, and they could have a business in there, says Robb from Merritt, which started their business in flex buildings.

Industrial buildings are typically used for the logistics industry the storage and distribution of goods or manufacturing. Industrial buildings typically also have a small amount of office space built into or adjacent to them.

Flex buildings offer a more equal mix of office and storage space, with 40-60% of the space dedicated to office or retail. Flex buildings are desirable by companies that need to accomplish some combination of making, storing, and selling their products, all in one space. That is why the space is considered flexible, they can do it all.

Why is industrial space important?

The industrial asset class is important because even though the manufacturing industry has declined in the United States, all consumer goods, regardless of country of origin, wind up moving through industrial space in the US at some point in their sales journey.

The flow of goods

Let’s walk through the journey of a widget that is manufactured in a foreign country.

First the raw materials for the widget are harvested or mined. These raw materials are processed in a plant near the source and prepared to be loaded onto a train for transportation. The initial processing and storing likely takes place in an industrial building.

Once loaded onto the train for transportation, the train cars are routed to the main processing plant several hundred miles away. When the locomotives and train cars need maintenance, where does that work take place? In an industrial building.

At the bulk processing plant the raw materials are stored and kept protected from the weatherin an industrial building. The raw materials are processed into refined materials, ready for various manufacturing processes. The refining process, of course, takes place in an industrial building.

The refined material that our widget is manufactured from is picked up on a truck at the plant and moved to a wholesaler’s warehouse. The refined materials, which may be of several different types, are stored and sorted by their various characteristics, ready for manufacturers to place their orders.

When the widget manufacturer places an order for the refined material (raw stock), it is taken from the warehouse and placed on another truck for delivery to the manufacturing plant. Just like the trains, the truck fleet is maintained in various industrial facilities.

The raw material delivery truck enters the manufacturing plant (an industrial building) and out of the other side of the plant comes a truck loaded with pallets of finished widgets.

These bulk widgets have already been purchased by customers, so the truck is driven to a distribution warehouse for the widgets to be stored and sorted with other products to be shipped out to customers.

Since our widgets are manufactured overseas, they will need to be shipped to the United States. Depending on the size of the order—a container full, a pallet full, a box full, or one part—the widgets will be shipped by boat or plane. Either way, they will enter the country at a port.

Regardless of whether they enter the country through a sea port or an airport, they will need to enter a warehouse to be stored, sorted, and tracked.

Once on land and through customs, our widgets will be loaded onto a truck and shipped with many other orders to a central distribution hub. This distribution and shipping will be handled by either the manufacturer (a first party company) or a third-party logistics (3PL) company who handles shipping, storage, and sorting logistics for multiple client companies.

Other than the transportation phase, almost everything that happens to our widget between the port and our manufacturing plant will take place in an industrial building. These operations could take place in a bulk storage facility, cross-docking facility, or distribution facility.

After the final truck is loaded with our pallet of widgets, the widget arrives at our small manufacturing facility. The pallet is loaded into the back of our flex space where we repackage our widgets or add them to a larger machine to be sold to customers in the retail portion of our flex space.

In this journey from raw material to retail, our widget has interacted with a dozen industrial facilities!

Development and investment factors

Given the large number of times that every product we purchase passes through the loading dock doors of an industrial facility, a lot of thought goes into the placement, development, and investment in the industrial real estate asset class. In addition, our region is experiencing a special season of high demand. According to Brown the market is white hot, unlike anything I’ve seen in the 35-years I’ve been active. Dunn adds that there’s a migration to the south, not only of population, but a lot of investors, their capital has been earmarked for the South and industrial.”

All industrial and flex buildings are owned by either landlord investors or end users. An end user, also known as an owner-occupier, could be any type of company or individual that would rather own than lease their space. Many manufacturing, logistics, and commercial businesses choose to own some or all of their industrial space.

If the facility isn’t owned by an end user, then it’s leased to the end user and owned by a landlord investor. Investors fall into two categories: private investors and public investors. If the investor is public, that means that the equity in their company is traded on the stock market. Private investors include any investment company whose shares are not publicly traded. Private investors can own portfolios that include just a single building or billions of dollars of industrial real estate.

Like all real estate investing, the industrial investment sector further breaks down into two main categories. There are companies that develop the real estate and companies that are long-term investors in the real estate.

Developers create value by finding sites, designing and building facilities, and then finding initial tenants for the facilities. They typically have a higher tolerance for risk than direct investors who don’t develop.

Investors create value through long-term management of the assets, by making improvements to older facilities and keeping buildings fully leased.

Some investors also do their own development work and are long-term holders of the assets.

When investors and developers are making decisions about where to build or how to handle their portfolio, there are many criteria that come into play.

Location

As the saying goes, the three most important factors for real estate are location, location, and location.

Truck transportation is critical to our land-based supply chain. Therefore, having industrial buildings located adjacent to major highway networks is critical. Highway proximity helps make it easier for truck drivers to enter and exit the facility. Dunn recommends anything that is easily accessible to [Interstate] 95 or [Interstate] 40 or any of the major thoroughfares that serve the eastern seaboard. If the facility is well positioned, the building signage will also be highly visible, acting like a billboard for tenants and end users.

Speed to market

For developers, the second most important factor is speed to market. If you can deliver something immediately, you have a much bigger advantage than someone who still has to pull a permit, it’s much better to be able to say, ‘we got you,’ ” says Robb.

Design and physical characteristics

As with all real estate asset classes, the industrial market is becoming more sophisticated. Increased sophistication and higher expectations from tenants, end users, and institutional investment partners is leading to changes in how industrial buildings look.

Square footage

Bulk storage warehouses are becoming larger, both in square footage and height. Buildings with more than 1 million square feet (almost 23 acres) of space under roof are becoming more common.

Clear heights

Clear heights, or the distance between the floor and the underside of the lowest portion of the roof system, are also increasing. Flex buildings typically have clear heights of 18 feet, and bulk warehouse space can have clear heights of 32 feet and higher. According to Brown, Ten years ago the market standard was 24 feet clear, now it’s more like 32 feet, some developers are building 36 feet clear. This increased height means a larger volume of goods can be stored in the same amount of square feet.

Volumetric storage space is especially critical to bulk storage facilities. The higher the clear height, the higher the racking systems can be. Dunn adds, An issue that can’t be remedied through [sic] is clear height. There are certain users that want to be able to stack their product. You have to have a certain clear height to serve those users. You can run into an issue sometimes if you are under 24 feet clear height.”

Building depths and bay depths

Building depth is also an important factor. Again, flex buildings are typically on the shallow end of the spectrum. Flex space typically is built with 80 feet to 120 feet of bay depth, which is the distance from the front door of the building to the loading dock in the back.

Cross-docking facilities are also typically shallow. A cross-docking facility is a special type of warehouse that has loading docks on the front and back. The goods come in on a truck and are sorted and placed directly on another truck. Cross-docking facilities don’t need much storage space, and the shallow depth reduces the distance a forklift needs to travel from one truck to the next.

Traditional industrial buildings have bay depths of 160 feet, with larger facilities having depths of more than 400 feet.

Truck courts and speed bays

In modern warehouse facilities, there are also changes happening in the space directly on either side of the loading dock door.

The truck court is the area meant for maneuvering, parking, and storage of tractor trailers on the outside of the building. Different facilities have different sizes and layouts of truck court. Modern warehouses with a high throughput of material and trucks need large truck courts.

On the interior side of the loading dock, Brown says that speed bays—wider bays by the truck courts—are pretty standard in the new buildings, in the past they were just 40-foot x 40-foot column spacing all throughout, now the bay closest to the docks might be 60 feet wide. A wider column distance in the speed bay leaves more open area for the maneuvering of forklifts.

Climate management

Another consideration for the modern warehouse involves insulation and mechanical equipment. Depending on the temperature requirements of the goods or operating environment a warehouse may or may not have air conditioning. If the building is conditioned, insulation is required on the walls and ceiling. Some warehouses are also specially built for even colder items. These buildings include large refrigerated and frozen sections.

Global Supply Chain

Shifts in global supply chains and inventory management practices also impact the industrial space business.

Bringing back manufacturing operations that were sent overseas is driving an increased need for industrial space, a practice known as onshoring.

Disruptions in the global supply chain caused by Covid-19 as well as other disruptions are also causing companies to increase the amount of goods they hold in inventory. With a decrease in just-in-time shipping practices, the demand for more physical space to store inventory is increasing.

E-commerce and the last mile

The rise in e-commerce is also directly impacting the industrial space business. With more items than ever being bought online, more items are being shipped from and between distribution facilities and to last mile facilities, where they ultimately depart on vans for home delivery. An increase in the number of distribution hubs drives up the demand for bulk storage space with larger truck courts, and the increased demand for last mile facilities drives the need for smaller buildings located near where people live.

Last mile facilities are also interesting because of the unusually high demand for parking. At the average industrial facility, it’s not uncommon to find a parking ratio – the number of parking spaces per 1000 feet of building area – below 1 per 1000 square feet. At last mile facilities, there is a higher number of employees involved in sorting the goods, as well as the need to park, move, and store a large fleet of delivery vans. At some last mile facilities, developers build more paved area for parking than building under roof, according to Brown.

Population Migration

As populations grow and move around the country, the industrial sector also grows and shifts.

North Carolina and the Triangle are experiencing substantial growth, as is the Sunbelt region as a whole. This growth impacts the industrial market on two opposing fronts: increased demand for warehouse space and increased competition for land.

Real estate development happens where there is demand and where the projects are feasible. Two very important feasibility characteristics are zoning and land cost.

Zoning

Zoning is established by the municipality and designates where certain types of buildings are allowed to be built, including industrial buildings. Industrial buildings are not allowed to be built everywhere. The amount of land zoned for industrial use can change over time, but the increase in demand for industrial space we are experiencing as the region grows is all competing for the same land. When demand increases and supply stays the same, pricing increases.

Demand for land from other asset classes such as residential, multifamily, and retail also increases the competition for developable land. Because zoning is often hierarchical, in many cases uses like office are allowed on land zoned for industrial – a lower use – but industrial is not allowed on all office zoned land.

Industrial properties are also inherently low density. In almost all cases industrial properties are single story, because it’s hard for a truck to back up to a loading dock on the second floor!

Land cost

Multistory construction for other building types, like multifamily, residential, retail, and office, allow more building space to fit on a plot of land. That means land costs can be spread across more building square footage. This distribution of land costs means that developers can spend less of their budget purchasing land, or they can afford to pay more for land because they can build more square feet of building per square foot of land to offset their upfront cost.

For example, if industrial land costs $10 per building square foot and a developer is building a 100,000 SF warehouse that needs 10 acres, the developer pays $1 million for the 10 acres or $100,000/acre. If a developer can build a three-story office on that same piece of land, they could get 300,000 SF of rentable space using the same total footprint of 100,000 SF. That means for every square foot of office space, the developer is only paying $3.33 for the land. If an office developer can afford to pay the same price per building square foot as an industrial developer, $10 per building square foot, then theoretically they can pay up to $300,000/acre for the same site. Because office tenants can afford to spend more on rent, office developers can often spend more on land, which exacerbates the problem for industrial developers.

Why would a seller ever accept $1 million for their site when they are able to sell it for up to $3 million? In this scenario there is no way the industrial developer will ever have success in buying that site, so they will have to try to build somewhere else.

With all the growth in our area and the premiums that other developers can pay for land, finding good industrial land is becoming more and more difficult.

Challenges for the industrial asset class

In addition to challenges on the land cost side of the development equation, the industrial asset class faces other challenges.

Historically industrial buildings and their uses produced pollution, noise, and other negative externalities. As a result, industrial buildings were banished to out-of-the-way locations, joining or creating the less desirable parts of town.

Regulatory changes have made modern industrial facilities much safer, cleaner, and less noisy than their predecessors, but the stigma persists. Customers want two-hour delivery—or faster—but generally don’t want warehouses near homes, shops, or green spaces.

Another challenge facing the industrial development industry is the availability of sites at any price that meet the requirements for space, slope, and buildable area.

As the region grows, large sites that industrial developers need are becoming scarcer. Sites that are flat enough for development, especially as building footprints increase, are also harder to come by. Additionally, the large sites that are still available are often bisected by streams or utility easements, constraints that make it harder to fit the building on the site.

State of the market

While the industrial space industry is experiencing challenges, the demand side of the market has never been stronger.

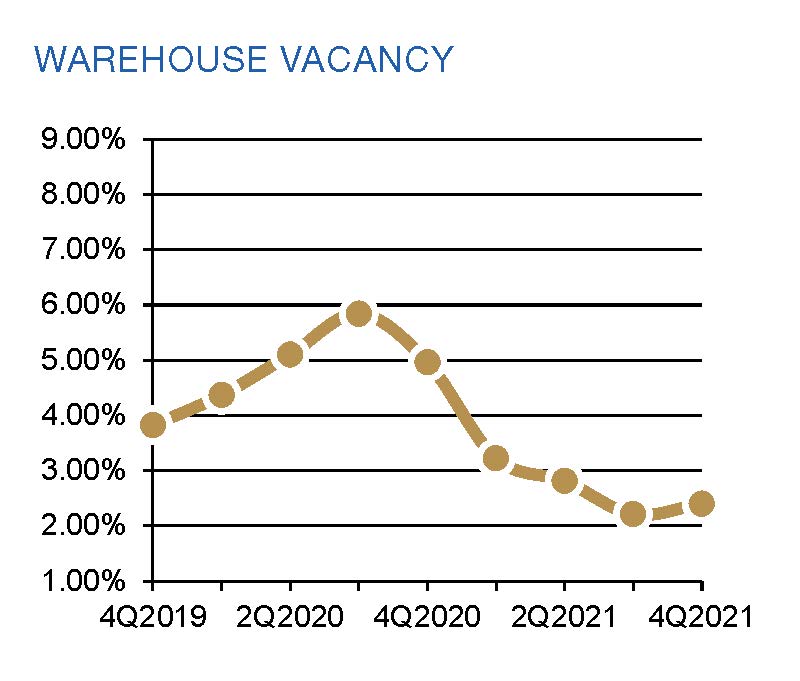

The long-term average vacancy rate for the industrial asset class is 8-10%. According to the 4Q2021 Triangle Market Report from NAI Tri Properties, current warehouse vacancy is 2.4%. The flex space vacancy rate is higher at 8.41%

There is 3.5 million square feet of space under construction that will bring the total industrial market size up to 39.8 million square feet.

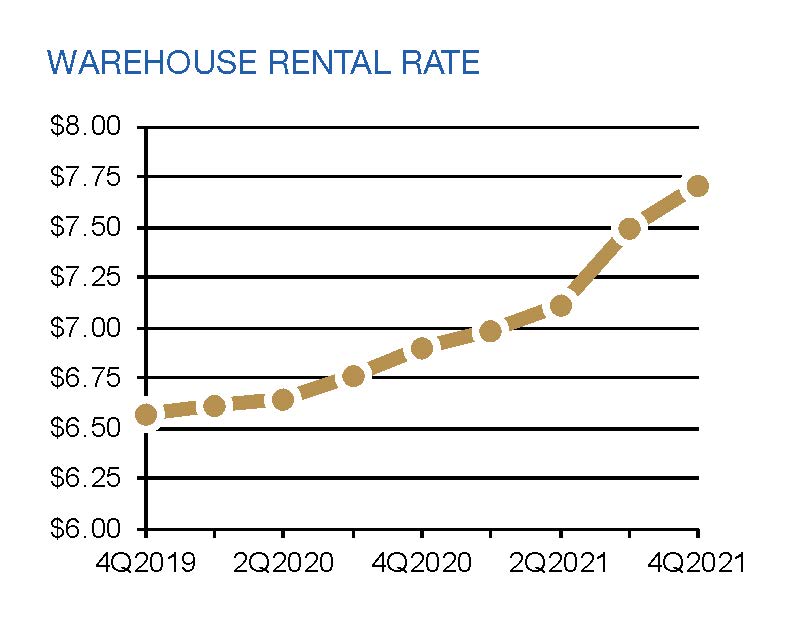

Industrial rental rates have continued to climb and are now at $7.71 per square foot; flex rates are up to $15.11. According to the NAI Tri Properties Report, Prologis has stated that across their portfolio in the US and Canada, rental rates increased 17.6%.

(Source)

(Source)

What’s next

The future of the industrial asset class looks bright. Innovations in automation and design as well as logistics will surely keep the pace of change and growth strong.

Like all markets, we expect to see a level of equilibrium where supply and demand meet, but looking at the current state of the market, I don’t anticipate equilibrium for several years.

Conclusion

I hope you have enjoyed learning more about the basics of the industrial asset class and hearing from our industry experts. If you have questions or feedback, I would love to hear from you. You can email me directly at jbyrne@withersravenel.com. Let me know what you learned from this article or where you would like further clarification!

Ed Brown, CCIM, SIOR

Ed Brown, CCIM, SIOR Valerie Dunn

Valerie Dunn Nathan Robb

Nathan Robb