Filter Portfolio

By Service Offering

By Project Type

Search Portfolio

-

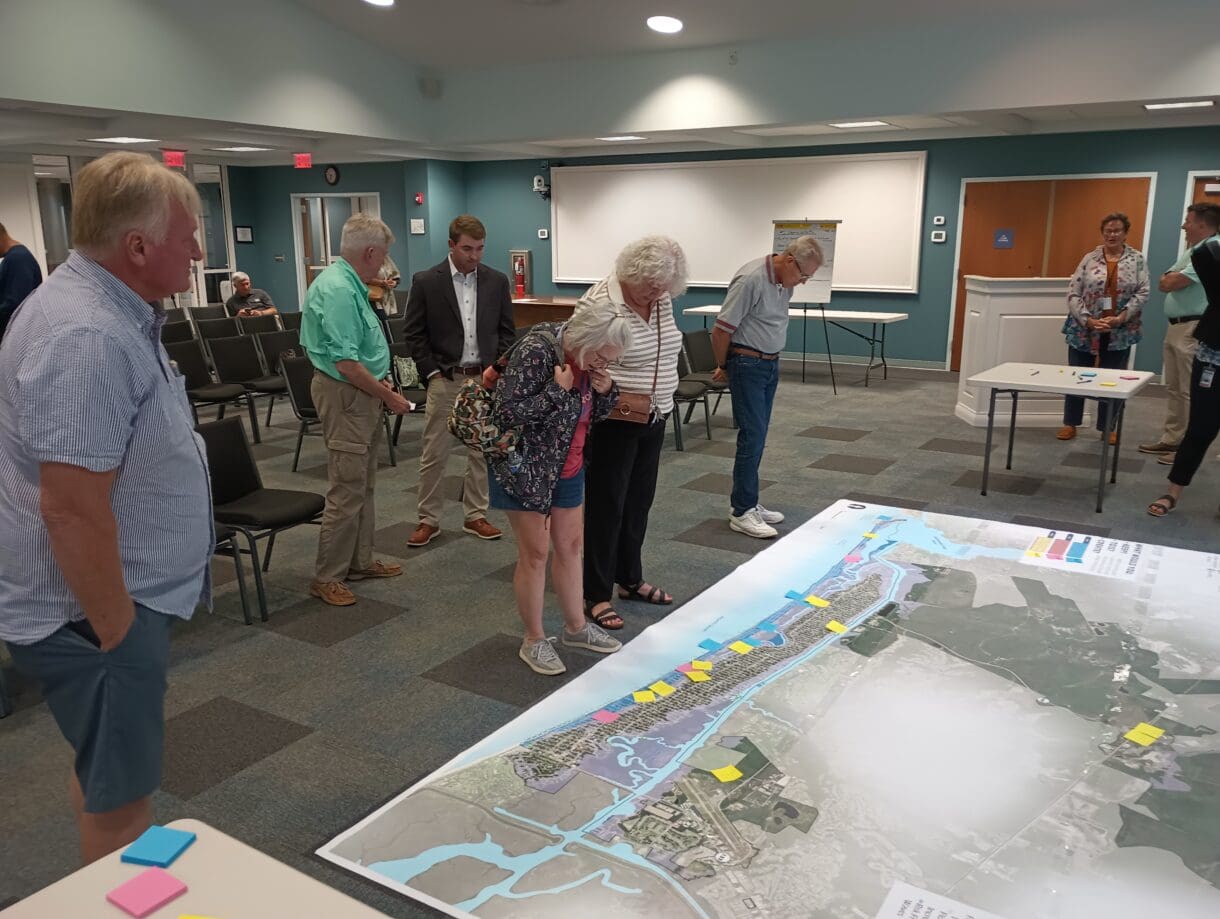

Oak Island, NC

Oak Island CAMA Land Use Plan

-

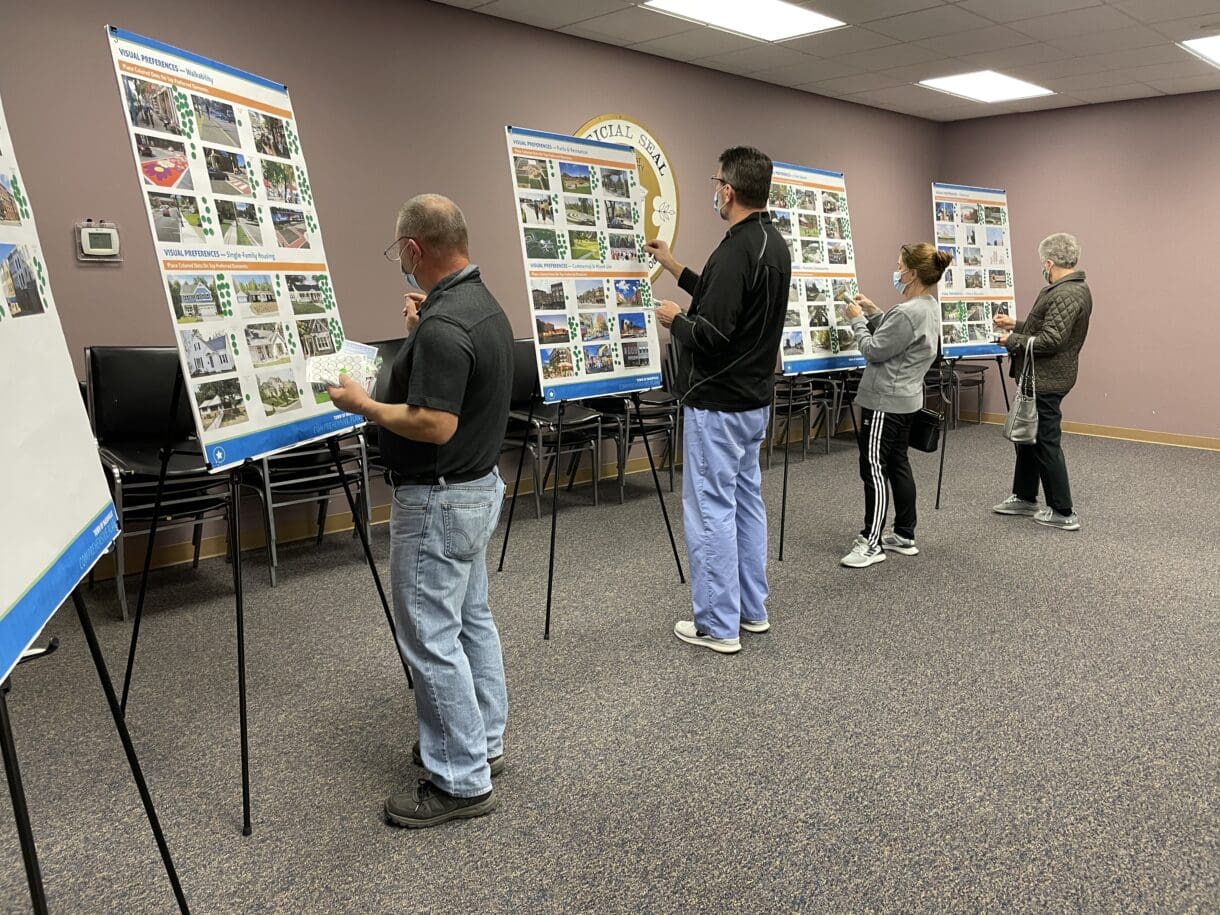

Town of Nashville Comprehensive Plan

-

Cary, NC

Town of Cary Fire Station 2

-

Ayden, NC

Ayden Concrete Plant

-

Gastonia, NC

Wastewater Treatment Facility Asset Assessment and CIP

-

Knightdale, NC

Knightdale Asphalt Plant

-

Maiden, NC

Wastewater Treatment Plant Assessment Report and CIP

-

Garland, NC

Wastewater Treatment Plant Improvements

-

Wendell, NC

Stormwater Utility Fee Advisory

-

Holly Ridge, NC

Dixon Water Treatment Plant Expansion, Final Design

-

Hendersonville, NC

Stormwater Fee Assessment

-

Pittsboro, NC

Chatham Park YMCA

-

Sanford, NC

Pilgrim’s Sanford Agricultural Marketplace

-

Apex, NC

Street Hockey Rinks

-

Rural Hall, NC

Rural Hall Parks and Recreation Master Plan

-

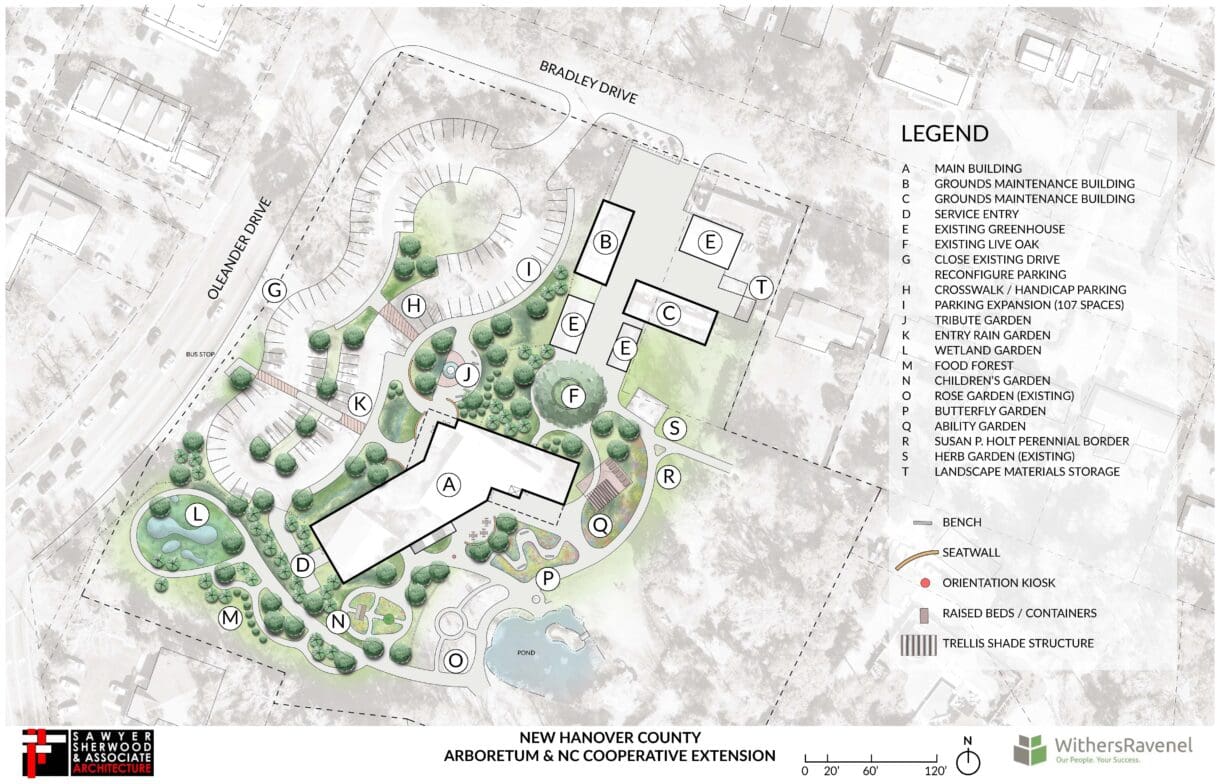

Wilmington, NC

New Hanover County Arboretum Master Plan

-

Lowell Parks Master Plan

-

Raleigh, NC

Crabtree Village Townhomes